As a Rails developer, you probably know what the following piece of code does.

# config/routes.rb

get "/about", to: "pages#about"

# controllers/pages_controller.rb

class PagesController < ApplicationController

def about

@title = "About Me"

end

end

# views/pages/about.html.erb

<h1><%= @title %><h1>As expected, it defines a route that directs a request to /about page to the PagesController#about method, which sets an instance variable @title that's displayed by the about.html.erb view.

Plain and simple.

Have you ever wondered how does an incoming HTTP request reaches the about method in the Rails controller? Like, who actually calls this method, what really happens before this method action is called? What happens afterwords?

This is something I used to be curious about ever since my ASP.NET MVC days, many years ago. But I never dared open the source code and take a peek at what was going on under the hood.

But now that I work with Rails, a framework written in the most beautiful (and readable) programming language (for me), reading the Rails source code has become one of my favorite hobbies, and in this post, we're going to learn exactly how a simple Ruby method is promoted to a Rails action, armed with magical super powers to process incoming HTTP requests and generate responses.

Before we begin, it's important to note that there are a few different ways in which you can direct a request to a controller action in Rails. In part one (this post), we'll explore the more explicit (and simpler to understand) approach, where we manually mark the method as an action. In the part two of the post, we'll explore the traditional and 'conventional' way (the example shown above), where Rails automatically figures it out.

I wanted to include part two in the same post, but it got way too big, and I doubt anyone would've stuck around till the end. So here it goes.

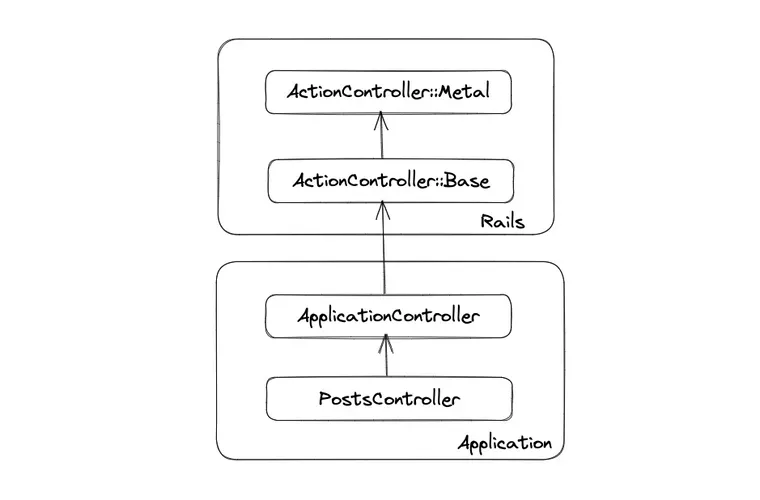

Let's begin our journey with the controller. To be precise, the great-grandfather of the PostsController class.

All Rails controllers in your application inherit from the ApplicationController class, which inherits from ActionController::Base class. This class itself inherits from the ActionController::Metal class.

The ActionController::Metal class is a stripped-down version of the ActionController::Base class. If you didn't know, you can use it to build a simple controller as follows:

class HelloController < ActionController::Metal

def index

self.response_body = "Hello World!"

end

end

All we're doing is setting the body of the response which will be sent to the client.

response_body above, will be covered in a future post.To use this index method as an action, we need to explicitly tell the router:

Rails.application.routes.draw do

get 'hello', to: HelloController.action(:index)

end

Note: To re-iterate, this is not how you write your routes in practice. I am just showing this to teach how a barebones Rails metal controller can handle requests.

So it seems like the action method does the heavy lifting of promoting a Ruby method index into a Rails action. Let's see what it does.

The action method

The action method returns a Rack application, an object that implements the Rack interface. To learn more about Rack, check out the following post.

Here’s the body of the action method. Remember, the value of name argument is :index, the name of the method in the controller.

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal.rb

# Returns a Rack endpoint for the given action name.

def self.action(name)

app = lambda { |env|

req = ActionDispatch::Request.new(env)

res = make_response! req

new.dispatch(name, req, res)

}

if middleware_stack.any?

middleware_stack.build(name, app)

else

app

end

end

The Rack application returned by the action method does the following.

- Create a new HTTP

Requestusing the Rack environmentenvobject. - Call the

make_response!method, passing the request. Themake_response!method generates anActionDispatch::Responseobject and assigns the request to it.

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal.rb

def self.make_response!(request)

ActionDispatch::Response.new.tap do |res|

res.request = request

end

end

- Finally, it creates a new instance of the controller class and dispatches (sends) the request and response objects to the action (

indexin our case).

new.dispatch(name, req, res)

new method, we're still in the context of a controller class such as PostsController, so think of the above code as PostController.new.dispatch(:index, req, res). Makes sense?To continue the above example, upon receiving a request to /hello, the Rails router dispatches the request to this Rack app. To be precise, it calls the action method :index referenced by the name variable, which builds and returns the response.

Let's see what the dispatch method does.

Dispatching the Action

The dispatch method takes the name of the action i.e. :index, the request object, and the response object as arguments. It returns the Rack response, which is an array containing the status, headers, and the response body.

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal.rb

def dispatch(name, request, response)

set_request!(request)

set_response!(response)

process(name)

request.commit_flash

to_a

end

The first two lines set the internal controller instance variables for request and response (for later use). Then, the process method, which is defined in the AbstractController::Base class, calls the action going through the entire action dispatch stack.

# actionpack/lib/abstract_controller/base.rb

def process(action, ...)

@_action_name = action.to_s

unless action_name = _find_action_name(@_action_name)

raise ActionNotFound.new("The action '#{action}' could not be found for #{self.class.name}", self, action)

end

@_response_body = nil

process_action(action_name, ...)

end

The process_action method calls the method to be dispatched.

# lib/abstract_controller/base.rb

def process_action(...)

send_action(...)

end

The send_action is an alias to the Object#send method, which actually calls the method associated with the action.

# lib/abstract_controller/base.rb

# Actually call the method associated with the action.

alias send_action sendTypically, you invoke the send method on an object, like obj.send(:hello) which will call the hello method on the obj instance. In this case, however, as we didn’t specify an object, it calls it on the self object, which is the instance of the HelloController. Hence, it calls the HelloController#index method.

Processing the Action

Now let’s inspect our index action method. All it does is set the response_body on self, which is an instance of HelloController.

def index

self.response_body = "Hello World!"

end

Let’s walk upwards in the stack. If you remember, our action was called by the AbstractController::Base#process method, which was invoked by the ActionController::Metal#dispatch method. Let’s continue where we left off in the dispatch method.

def dispatch(name, request, response) # :nodoc:

set_request!(request)

set_response!(response)

process(name) # **we are here!**

request.commit_flash

to_a

end

After calling process(name), the response_body is now set. The Request#commit_flash method deals with the flash, which we’ll ignore for now. Finally, it calls the to_a method, which delegates to the to_a method on the response.

def to_a

response.to_a

end

Sending the Response

The ActionDispatch::Response#to_a method turns the Response into a Rack response, i.e. an array containing the status, headers, and body.

def to_a

commit!

rack_response @status, @header.to_hash

end

The rack_response method generates the body using the RackBody class, which responds to the each method, as it’s part of the Rack specification.

each or call. A Body that responds to each is considered to be an Enumerable Body. A Body that responds to call is considered to be a Streaming Body.def rack_response(status, header)

if NO_CONTENT_CODES.include?(status)

[status, header, []]

else

[status, header, RackBody.new(self)]

end

endSo, ultimately, that’s how our simplest metal controller sends the response to an incoming HTTP request.

If you're curious, read the following post to learn more about the Rails rendering process.

This post was inspired from Phil Haack's post 16-year old post: How a Method Becomes an Action (in the context of ASP.NET)

That's a wrap. I hope you found this article helpful and you learned something new. In the part two of the post, we'll explore the more conventional way in which a request is routed to an action method.

As always, if you have any questions or feedback, didn't understand something, or found a mistake, please leave a comment below or send me an email. I reply to all emails I get from developers, and I look forward to hearing from you.

If you'd like to receive future articles directly in your email, please subscribe to my blog. Your email is respected, never shared, rented, sold or spammed. If you're already a subscriber, thank you.